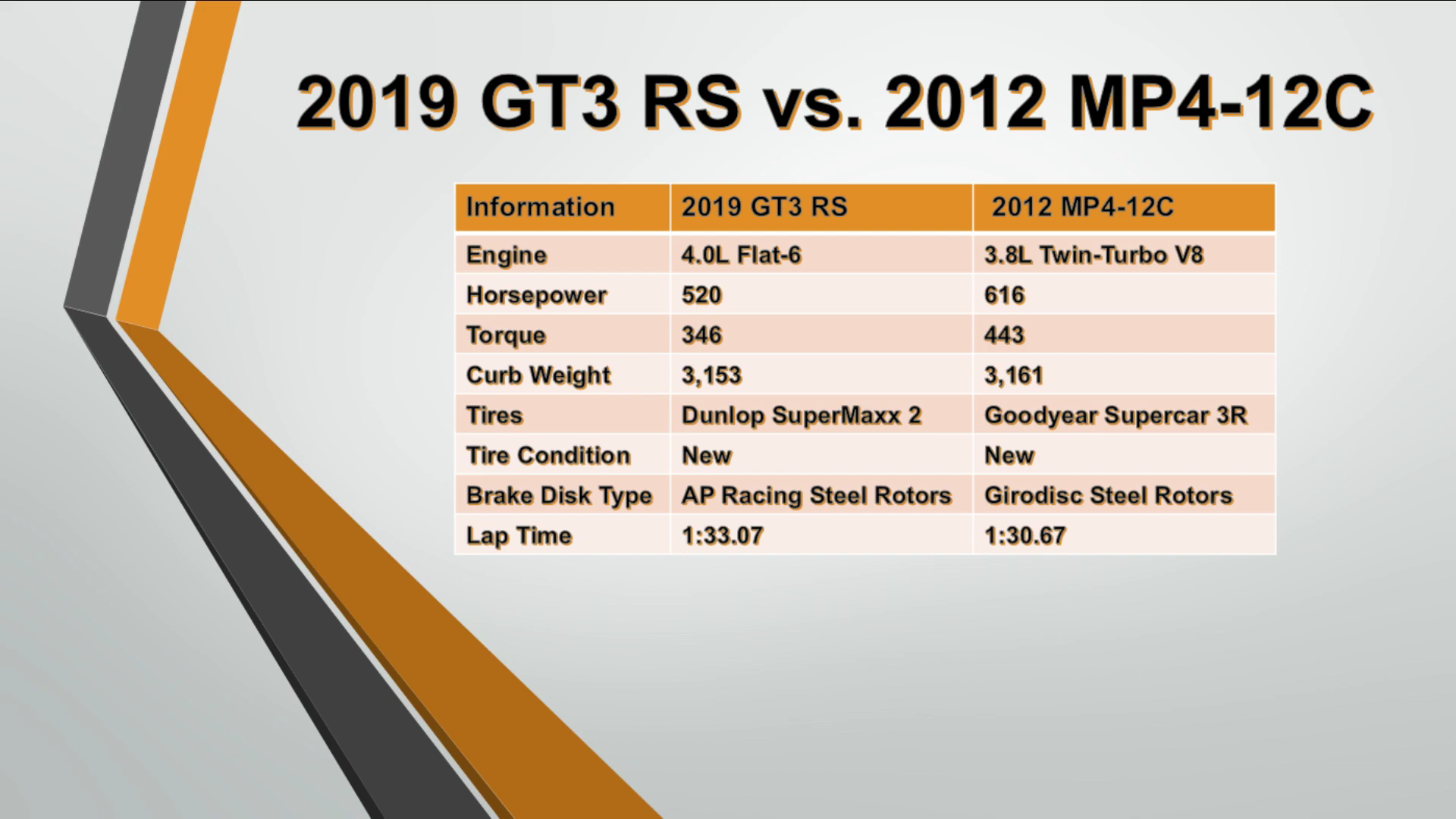

A better comparison could not be had. Two talented, technically savvy drivers, two of the best sports cars on the market, the right tires, and the right conditions amount to an assessment that his as entertaining as it is informative. In the McLaren MP4-12C is Jeffrey Cook, a young racer and driving coach who’s recently made the McLaren his designated track toy after selling a Camaro ZL1. In the GT3 RS: Joe Kou, a Spec Miata racer and trackday fanatic who keeps the green Porsche on hand for weekends when SCCA events aren’t taking place.

The cars are similar in weight, but very different in most other ways. Weight distribution, tire size, power delivery, and aerodynamics all make major differences in how these two get around a track. Of course, there’s the abundance of power the McLaren has—something which makes a major difference at a power circuit like Laguna Seca, but the atmospheric Porsche has a few strengths which help make up for its moderate amount of power. You’re in good company when your Porsche GT3 RS is described in any way as “moderate.”

The Difference in Design

With less downforce and two turbochargers to propel it, the McLaren is predictably much quicker along Laguna’s straighter sections—roughly 6 miles per hour down the straights preceding Turn 2 and Turn 8. That’s something considering how the Porsche, the car with much more mechanical grip and a more urgent motor, is regularly the car faster from apex to exit.

The Porsche’s massive footprint—sporting 325-section rears and 265-section fronts—is far larger than the McLaren’s 305 and 235, respectively. With the exception of Turns 2, 6, and 11, the Porsche is much quicker through the corner. The overall level of mechanical grip is reassuring, and it also allows for a little more sliding, interestingly enough. It’s not usually the case that the car with the wider tires benefits from more slip angle.

The Porsche’s downforce plays a significant role here. In sweeping bends like 2, 4, and 5, the Porsche is faster, but perhaps the greatest indication of downforce’s value here is in Turn 9. After the McLaren beats it to the long, downhill left by an addition 9.9 mph (the largest vmax spread anywhere on the track), the Porsche returns with an addition 3.9 miles per hour through the middle of the corner. The same is seen in Turn 10—even more thanks to the slight banking which, like a hammock, catches the car as it makes its way to the apex.

The way these two charge towards and through Turn 9 (5:37) tell the whole story.

That high-speed stability is where the Porsche’s minimum speeds is at its relative highest. On slower bends, the McLaren’s mid-engine layout is ideal; less moment of intertia helps it tuck the nose in, even with narrower front tires. That said, it’s a matter of feeling with Cook; he feels the lack of tire holds it back slightly, but the overall balance of the car is better suited to these slow corners.

Difference in Technique

That said, it’s a little more challenging getting the McLaren to turn. The smaller front tire and absence of rear-wheel steering means the McLaren won’t necessarily rotate into the corner unless treated a certain way. Basically, this calls for a longer trailbrake, which is made more complicated by the fact that the McLaren’s brakes aren’t the easiest to modulate. “They’re either on or off,” Cook remarks.

Getting the McLaren from apex to exit cleanly is even more challenging. The abrupt surge of torque around 4,000 rpm is enough the lift the front of the car and cause a little power-understeer everywhere but the slowest corners. To keep the platform as balanced as possible, Cook had to retrain himself to begin applying throttle earlier than his intuition would urge him; the lag and mid-range boost means the power delivery doesn’t correlate intuitively with the travel of the throttle pedal.

At the top of the hill, just look at the difference of the steward’s tower on the left.

When done correctly, the McLaren is reasonably straight by the time the boost arrives. Without this concern, the Porsche is arguably the easier car to drive. “It’s wild how the latest 991 GT3 RS is so capable,” Cook begins. “For the amateur driver, it might be the best trackday car around. As long as they can get used to the rear-engine dynamics and the throttle control at high speeds (learning to trust the rear moving around), it’s so straightforward and much easier to get near the limit.”

The McLaren is less accommodating and requires a deft touch to find the limit. “A lot of people get frustrated with the way the power comes on and think they’re at the limit when they’re not.” Approaching the limit prematurely was one thing Cook had to overcome himself. “I think it’s made me smoother driver—you have to be, because once it starts to slide much, you lose a lot of time.”

If the McLaren is tamed, it’s a quicker car than the more agreeable Porsche. However, the spread seen between these two laps above isn’t completely indicative of the cars’ abilities. “I think if I was driving the GT3 RS, on these tires, I’d be able to get a 1:32.4 or thereabouts,” Cook asserts with some modesty. Kou is very talented driver as well–no question about it, but Cook is the professional coach.

There are plenty reasons to like either car, and getting to see how these cars find their lap time makes them even more appealing. Personally, I prefer the scream and the urgency of the Porsche over the McLaren’s incredible torque, but I might be a little biased.