Dobson enjoying his only stint at Le Mans.

In 1989, Dominic Dobson already had a few years’ experience in the Porsche 962. With Bayside Racing, he’d campaigned one of these cars in IMSA GTP and learned its nuances. That year, his team received a call from Vern Schuppan, who was looking to recruit an American driver for his Le Mans effort. Dobson duly signed, and flew off to France to join an all-star lineup.

He would partner with Will Hoy, the British touring car ace, and Jean Alesi, who’d just won the F3000 championship and was the unofficial star of the team. Dobson took the Takefuji 962 out for its second stint as the sun began to set in France. Hurtling down the Mulsanne Staight, all felt well. However, upon braking for Arnage, the right-hander leading onto the Indianapolis Straight, he sensed the car’s rear end quaver slightly—though not enough to cause alarm.

Hurtling down the Indianapolis Straight, Dobson caught the scent of smoke and by the time he’d engaged fourth gear—somewhere north of 110 miles an hour—he saw flames. A faulty fitting in the fuel system caused one of the fuel lines to spray onto one of the red-hot turbos at 120-odd pounds of pressure. With the perfect improvised flamethrower spewing away, soon the brake lines had melted completely.

Dobson, struggling to shut down the blazing prototype, prodded the middle pedal to no avail. The brakes were useless, and soon the rear began to sway wildly; the toe link had melted in the blaze. Downshifting to try and stop with engine braking did little good, and the barrier on the left looked like the best way to bring the car to a halt.

As he ground to a halt, he triggered the fire system which did very little. Undoing the belts with smoke starting to flood the cabin, Dobson—now painfully aware of the flames creeping around the firewall—tugged at the door straps with as much clarity as someone flammable in that situation can. His first attempt to exit failed; he hadn’t fully undone the shoulder harnesses, and the door closed on him in the pandemonium. Holding his breath, he pressed himself into the backrest, slipped the harnesses off, and felt once again for the door strap; thick smoke kept him from seeing much at that point. Fortunately, he found it!

Standing on the other side of the guardrail, he watched his only attempt at Le Mans go up in flames and several course workers struggle to quell the fire. One worker—not the sharpest knife in the drawer—began spraying his extinguisher thirty feet before he reached the car, and another slipped on the thick layer of white soot lining the track. Despite the yellow flags waving and the white cloud surrounding the site, cars continued through at 130 MPH-plus. “Nobody observes the yellow flags in Europe,” recalls Dobson with obvious mirth, “it’s seen as a chance to make up a place or two.” More surprising than the car not roasting completely: that none of the marshals were killed.

As French television cut to another scene the first time the door closed on itself, his team were unaware of Dobson’s condition. As they fretted in the pits, Dobson was trekking through the French forest in search of a ride. Ninety minutes later, an uncharred Dobson wandered back into his pit box to the delight of his bemused but relieved team.

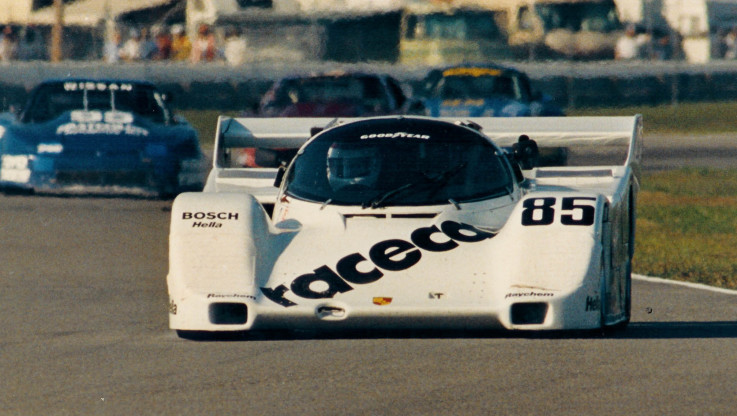

Dobson enjoying a cooler drive in the IMSA-spec 962 at Sebring.