(Editor’s note: This weekend the world celebrates the 105th running of the Indianapolis 500. Years ago we ran three features on major Porsche efforts at Indianapolis, and we’re re-running them today. While Porsche has had varying degrees of success at The Speedway in years gone by, we remain hopeful that one day the company will again expand its efforts into the greatest spectacle in motor racing. For now, please enjoy The First Porsche At Indianapolis, Politics Prevent Porsche Participation At 1980 Indy 500, and Porsche’s Project 2708 at Indy.)

Porsche has a long history with racing, but by 1966, they still had not ventured into the oldest motoring event in the United States, the Indianapolis 500, and would not for another 14 years. One of the most grandiose spectacles of all time, the Indy 500 has been held at the “yard of bricks” since 1911. By the mid-1960s, most of the privateer racers had died off, and the manufacturer era was in full swing. Occasionally, though, a privateer would show up with a hair-brained scheme that they had cooked up in a dimly lit barn over the course of the previous winter, hoping to overthrow the might of a major team with brains, instead of brawn. This is one of those privateer, underdog stories.

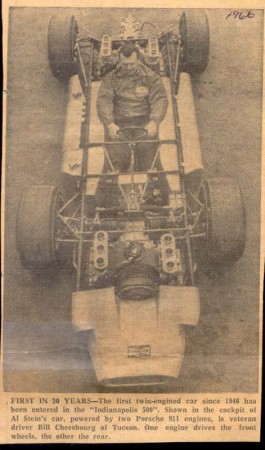

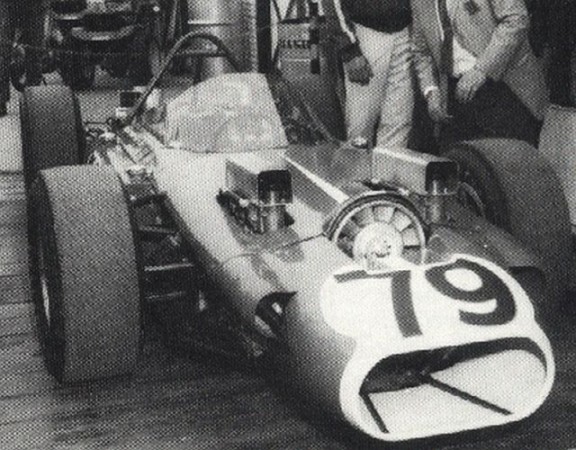

The Stein-Porsche Twin, showed up at the track to little fanfare. Albert Stein, a midget racing champion from Southern California, saw the simplicity and power available from Porsche’s flat-six, and wanted to exploit these traits in his attack on the long straights of Indy. Pulling from lessons learned in the past, Stein brought back the “twin engine roadster” design that had disappeared from the speedway 20 years prior. His hopes were that the lighter individual weight, lack of liquid cooling system, and lower center of gravity of the flat engines, combined with the added advantage of four wheel drive, would provide the necessary benefits to overcome the ungainly front engine placement and added weight of a second engine.

Stein hired Joe Huffaker to assemble a suitable chassis for the engines, and cribbed a pair of transmissions from Lancia’s racing division, giving him the basis for his assault the following spring. Stein had planned to use a more traditional Ford or Offenhauser engine setup, but in the planning stages, a friend in Europe offered three 2.0 liter 901 engines for less than the cost of a single example of one of the “Americans”. Albert had one of his crew fabricate an aluminum body shell for the car and used traditional Indianapolis racing brakes from Girling, and a set of lightweight magnesium wheels to complete the build.

In an odd setup, the front engine was faced frontward, with the Lancia gearbox facing the driver’s seat, while the rear engine was also faced frontward, with the engine immediately behind the driver, and the transaxle out back. Out of necessity, the gearboxes were required to be built identically, and a strange erector-set of shift linkages, clutch operating levers, and throttle cables were needed to synchronize both drivetrains together. Obviously, the front engine supplied power to the front wheels, and the rear engine supplied power to the rear wheels, but both engines could be operated independently from each other, should one of them fail.

Experienced, but not necessarily qualified, driver Bill Cheesbourg, was elected to drive the car at the Speedway. Cheesbourg had participated in every Indy 500 for the preceding 9 years, yet had only qualified for the 33 car field six times, and four of those occasions he started on the last row. While Cheesbourg had finished in the top ten in 1958, this was a minor victory, as it was predominately down to the attrition rate in the remainder of the field.

During qualifying for the race, Bill was able to foot the car around the course at an average speed of 149 miles per hour. He tried a number of times, yet was not able to go any faster. On scene reports suggest that most of the qualifying session was spent fiddling with the car, attempting to make things work as they should. It was evident that the car was not as quick as they had hoped, and as last gasp effort to turn up the wick didn’t pan out. The team would not make the “big show”, failing to make the final row by nearly 10 miles per hour. The car, according to Cheesbourg, was lacking predominately in power, as he claimed he could drive with his accelerator pedal flat through all four of Indianapolis’ famous ninety-degree corners. Carrying momentum was not the problem, gaining speed on the long straights, however, was.

Stein claims that he was negotiating with Porsche to have “911S” camshafts installed in both of his Indianapolis engines, yet was told that they were not willing to release them for sale as the production cars had not yet hit the market. If Bill Cheesbourg’s claim of flat-footing the corners is true, I believe the additional power provided by the cam update could have given the car the added oomph it needed to make the race. Stein remained adamant of this for many years after they had packed up and gone home, post-qualifying effort.

What Happened To The Stein Porsche Twin

Stein made an effort to return the next year, offering to sell the operation to anyone for a “nominal dollar” if they promised to fund the effort in 1967. Unfortunately, nobody took Stein up on his offer, and the car was eventually dismantled and sold for parts. Pieces of the aluminum bodywork can still be found in race shops across Southern California. If a few variables had been slightly different, I like to think that this car could have found its way into a museum, rather than the unsanctified end that it met. If Porsche had released the “S” cams, if Stein had hired a more qualified driver, if they had been able to work out all of the issues, might Porsche have become more synonymous with Indy? Might they have spent their late 60’s factory racing efforts focused on Indiana, rather than Le Mans, France, fighting Ford and Offenhauser, rather than Ferrari?

Here’s How You Can Get More Porsche Info Like This

Most of the information for this post comes from ‘Porsche Specials’ by Jurgen Barth and Lothar Boschen. While out of print, it’s still available on Amazon from 3rd party sellers and is full of interesting Porsche trivia.

Updated (11:37am EDT, 5/24/2021): Updated for 2021 Indy 500 week, added intro paragraph.

Other Porsche Blog Posts You Will Enjoy

How The 909 Bergspyder Impacted Porsche’s Racing And Development History

3 Porsche Wagons From Years Gone By

Are The Rumors That Porsche Plans To Build An Off-Road ‘Safari’ Version Of The 911 True?