(Editor’s note: This weekend the world celebrates the 105th running of the Indianapolis 500. Years ago we ran three features on major Porsche efforts at Indianapolis, and we’re re-running them today. While Porsche has had varying degrees of success at The Speedway in years gone by, we remain hopeful that one day the company will again expand its efforts into the greatest spectacle in motor racing. For now, please enjoy The First Porsche At Indianapolis, Politics Prevent Porsche Participation At 1980 Indy 500, and Porsche’s Project 2708 at Indy.)

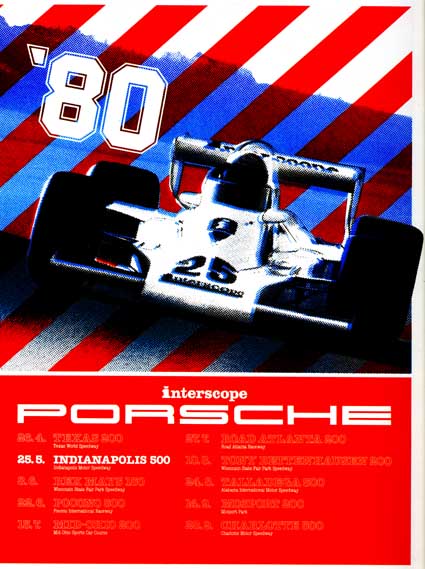

In mid-1979, a committee at Porsche decided that the company would front an assault on the Indianapolis Motor Speedway the following May. As Porsche already has a proven reliable and powerful engine in their 935 endurance racing flat-six, only slight modifications would be necessary for eligibility at Indianapolis. Starting their program with an existing, if slightly less than leading edge chassis design, and working with an established and promising team in the form of Interscope Racing, Porsche’s chance of being a contender was quite high, fresh out of the box.

Interscope Racing had, by this point, a very close working relationship with Porsche motorsport, having run endurance 935s all over the world for the previous 4 years, culminating in a Daytona 24 victory in early 1979. Porsche was working with a known commodity, having seen how quick Danny “on-the-gas” Ongais could be when given a well set-up car. Equally, Interscope knew the resources and engineering know-how that could be made available to his team in a partnership with Porsche. Neither side was on the losing end, yet both knew how much they had to gain from working together.

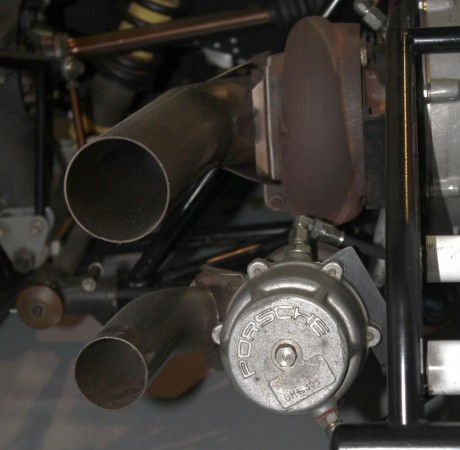

The Porsche developed engine for the USAC/CART world took advantage of experience gleaned in other forms of racing. Previous failures had taught Porsche that the cylinder heads needed to be water-cooled for longevity, yet for weight savings and simplicity, the cylinders should remain air-cooled. High peak boost pressure was only possible with this engine once the cylinder heads were “electron-beam welded” to the top of the cylinder, and installed as an assembly. Using a 2.65 liter version of this engine allowed them to use significantly higher boost pressures than their competition. While the information was never truly made public, it is believed that Porsche’s engine was capable of producing north of 800 horsepower, and could survive sustained engine acceleration north of 9000 rpm for hours at a time.

With the engine sorted, and known to be reliable, Porsche selected an equally reliable and well known chassis. Working with Interscope afforded Porsche immediate access to years of oval track setup knowledge, as well as access to a modified VPJ Racing-based design, dubbed the “Interscope PGB”. Interscope’s chassis was a standard aluminum construction monocoque with a tubular rear drivetrain subframe. By this point, both Penske racing, and Jim Hall’s Chapparal team had developed “ground-effect” based chassis which had proven to be difficult to keep up with.

From the outset, there was internal opposition in Germany to the project in the form of Ferry Porsche.

Ernst Fuhrmann, then Chairman of Porsche, had sided with Vasek Polak’s recommendation to work with Ted Field’s Interscope racing, with prodigal Ongais as the driver. Ferry had been wary of open wheel racing for several years, having ended Porsche’s open wheel program in 1962 to concentrate on sportscars like the 904. Equally, Ferry’s close personal adviser, and retired head of motorsport, Huschke Von Hanstein had been opposed to teaming with Interscope, preferring to work with Dan Gurney’s All American Racers. In the end, Fuhrmann signed the deal with Interscope.

In early spring of 1980, Porsche had already conducted several successful private tests of their new Indy contender. These tests included an outing at Ontario Motor Speedway in California where the new car shattered the track record. This was important, primarily because Ontario boasted a near identical copy of Indianapolis’ layout. These tests were only witnessed by Ongais who drove, Field who owned the car, and a handful of Porsche and Interscope team engineers, though it is rumored that spies and informants from other teams were also secretly in attendance.

Decidedly worried that the new Porsche engine was the better of the Cosworth engine in his car, A.J. Foyt began lobbying with USAC to reduce Porsche’s allowable boost levels. Porsche Motorsport had built the engine to produce the allowable maximum of 54 inHg (about 1.83 bar), and Foyt wanted to have the engine restricted to 48 inHg (about 1.62 bar).

Being that Foyt was one of the few remaining internationally-known open wheel superstars to not jump the USAC ship in favor of CART, it was in USAC’s best interest to keep Foyt as happy as they reasonably could. USAC, until this point, had been hopeful that Porsche would become another factory engine supplier to the series, offering off-the-shelf solutions for other teams wishing to install Porsche engines in their own chassis. When the Foyt protest was lodged, USAC asked Porsche bluntly whether they would be capable of providing engines for teams other than Interscope, the motorsport department responded that they were capable, but uninterested in doing so.

Nearly immediately after Porsche’s reply, the USAC board of directors voted to lower the allowable intake pressure for the Porsche engine to 48 inches of Mercury, causing a great decrease in the engine’s maximum power output. Finding themselves less than a month from the Indy 500 without a competitive engine, and a chassis they believed incapable of victory, Porsche issued a harshly worded single-page press release. The release declared their withdrawal from the 500 with immediate effect, citing a lack of time to test at the new lower boost pressure as their reason.

Interscope Thought Porsche Could Still Be Competitive

Ted Field of Interscope, fearing that the decision would be finalized soon, conducted a test session of his own at the new lower pressure. His finding was that, while the car was slower, it was not slow enough that the car could not be made competitive. Still wanting to make a go of it, Field expressed this to Porsche, and the response was overwhelmingly negative. Porsche was done, and nothing he could say would make them change their minds. Field believed that his contract was still solid, and that Porsche would need to fulfill it by continuing to supply his team with engines for the remainder of the season. Field filed legal action against Porsche, and a settlement was reached out of court. Still needing funds to continue the season, Interscope sold one completed chassis, one backup chassis, and one show car to Vasek Polak, who stored them at his California warehouse until his death. The project was shelved before it had begun in earnest, and the cars were put into storage before they had ever turned a wheel in anger.

When Polak’s estate became available, the one complete chassis (USAC number 0031) entered the market, and after passing through a few other hands, ended up in the famous Matt Drendel Turbocharged Porsche collection. The car received a complete 100 point restoration by Gunnar Racing in 2002, and remains in perfect condition. The car is now used almost exclusively for static display, but is occasionally started and run for the enjoyment of the public. As with the rest of Drendel’s collection, the 1980 Interscope Indianapolis Championship car was included in the Gooding and Co auction from Amelia Island in 2012. With a pre-auction estimate placing the car’s value between $350,000 and $550,000, the car looked promising, but went unsold by auctions’ end.

Updated (11:41am EDT, 05/24/2021): Updated with 2021 Indy 500 feature text.

Other Porsche Blog Posts You Will Enjoy

The First Porsche at Indianapolis

Why Porsche Should Revive the Front Engine Sports Coupe

Video: “Living The Porsche”

[Photos: Gooding and Co. / Porsche / Bradley Brownell | Source: Autoweek (Dec 31, 1979) and Panorama (Sept, 2002)]